Performance from the head or the heart?

(originally published 11/21/21 in the IfCM newsletter)

I wasn't ready to be inspired by or even interested in the writing of George Saunders. I was listening to the actor/author/carpenter Nick Offerman's travelogue Where the Deer and the Antelope Play because it included a LOT of things that I'm already interested in. Hiking in Glacier National Park? Check, of interest to Chris. Misadventures involving heavy machinery? Yes, that's included. Pithy jokes and swears? Double check. This is a great book to listen to while hanging out with my 6-month old during the day and re-affirm things I already enjoy. But hold on, part of the book includes two of Nick's good buddies joining him on a hiking trip and I get to learn a bit about them. The first, Jeff Tweedy, I know a bit about. George Saunders is his other hiking companion and I had no frame of reference, so I decided to check out his most recent book from the library. Sigh... At first glance, the book seems like it will be like school I'm not good at. A reading of four short stories by Russian masters Chekhov, Turgenev, Tolstoy, and Gogol and a breakdown by writer and teacher Saunders? This is not what I usually get into. But hold on, it definitely is. This book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is my new favorite thing. I had previously been a failed reader of the Russian masters (I just checked my decades old copy of Crime and Punishment and the bookmark sits at page 152). Now I might consider getting Tolstoy's face tattooed on my face. And then George Saunders's face tattooed on top of that.

Ivan Turgenev. Probably reaching for a snack in his pocket.

Ivan Turgenev's short story The Singers narrates an impromptu vocal competition in a small rural pub. The first participant, known as "the contractor", performs a virtuosic number, amazing the listeners with his technical prowess. He "didn't lose himself, or forget about his audience, or surrender to a feeling; sensing victory, he unleashed a higher-level arsenal of charming tricks. (He acted at his audience, rather than upon them)." The second singer, Yashka, is nervous. Saunders relates that:

"his first note was faint and uneven." It seems to have come floating into the room by accident" (the opposite of technical prowess)...his voice is broken and cracked, and it has "an unhealthy note in it," but also "genuine deep passion, and youthfulness and strength and sweetness." Soon, Yashka is overcome by ecstasy." He seems to lose awareness of himself and his audience, gives "himself up entirely to his feeling of happiness."

Yashka acts upon his audience, rather than at them. The listeners in the pub weep uncontrollably at his performance. Yashka wins the informal competition in a landslide.

Yashka probably looked like Turgenev. This is an award he could have received.

Technical prowess and musical "feel" are two parts being a good musician. Technical ability is very commonly assessed and measured. Can you play the melody to "Donna Lee" at 300 beats per minute? You can answer yes or no and provide a measurement (No, but I can play it at 250 bpm). Do you know 3 Charlie Parker solos and can you deploy 10 ii-V licks in all 12 keys? (Yes, and I have created 5 new variations on his licks!)

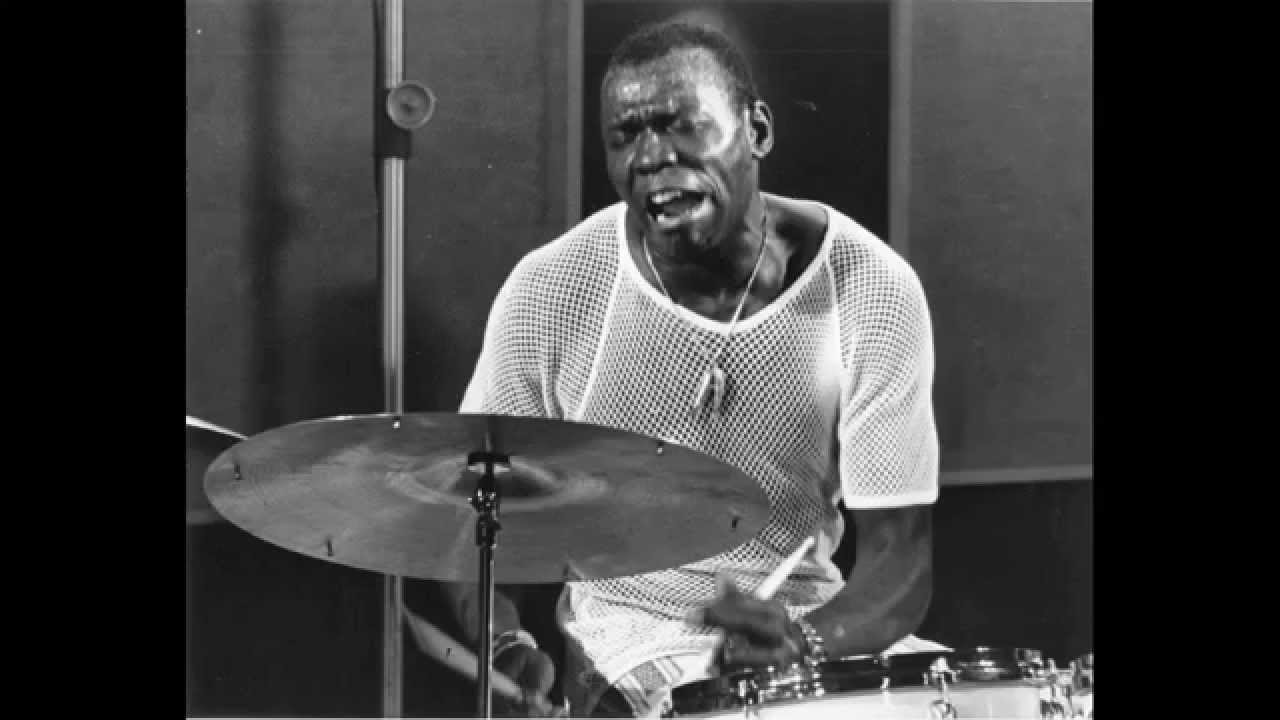

All of these technical things are very hard to do, take hours of practice to master, and (in a lot of cases) are the bare minimum to being considered a competent professional jazz musician (sheesh...). On the other hand, how to we measure and practice our "feel" and ability to connect with other musicians and listeners? Shoot. That's harder to teach and quantify. Listening to great music over and over again helps, as does playing along to recordings and with other musicians. But there's something that isn't really measurable about feel in the same way as with technique. Why is drummer Elvin Jones's feel so interesting and emotive? Hmmm...he phrases his ride cymbal beat in a certain way that we could sorta be put on a mathematic grid and I could try to copy it...but that doesn't quite do it. Saunders hits on this ineffable feeling that happens when we're trying to explain something like this:

"We're rationally explaining and articulating things. But we're at our most intelligent in the moment just before we start to explain or articulate. Great art occurs--in that instant. What we turn to art for is precisely this moment, when we "know" something (we feel it) but can't articulate it because it's too complex and multiple. But the "knowing" at such moments, though happening without language, is real. I'd say this is what art is for: to remind us that this other sort of knowing is not only real, it's superior to our usual (conceptual, reductive) way."

Nailed it, George. There's the "knowing" of art that comes from appreciation and application of the technique involved and there's the "knowing" that is left on the tip of your tongue and can't really be expressed in words. Experiencing something like Yashka's song or Elvin Jones's...Elvinness...is what it is. Hopefully we can all experience things like this with others and appreciate that it is ineffable.